Snorkeler's Guide to the Black Sea

Author: Todor Iordanov

Email: todor.iordanov@hippocampus-bg.org

Many divers from Western Europe expect the Black Sea to be boring and monotonous. Rumor has it that there is less biodiversity compared to the e.g. Red Sea, that the fish are not very colorful and that visibility is not good. Some of these preconceptions have some truth to them, but things look different if divers have enough patience to take a closer look at the Black Sea.

Purpose of the following guide is to help novice divers exploring the Black Sea. “Divers” does not only address scuba divers, but also all curious big and small marine explorers who spend long hours with mask, snorkel and fins at sea during their summer holidays.

It's hard to describe all that can be seen under water in the Black Sea, it is even harder to see everything the sea has to offer. I cannot say that I have seen everything under water, but I would like to share what I have managed to see.

I've been diving in the Black Sea since childhood, and I'm still not bored. When I was a little kid, my guide was (and still is) my father and diving instructor Gerdan. Before getting into the water, my father would give me instructions like: "Look for a weever on sandy bottom and for a scorpionfish on rocks." Or "When you're free-diving you have to wait at least a minute and a half under water for the mullets to appear." Almost always, my father was right and most of the things about the sea I have learned from him, but I also learned a lot from my own experience.

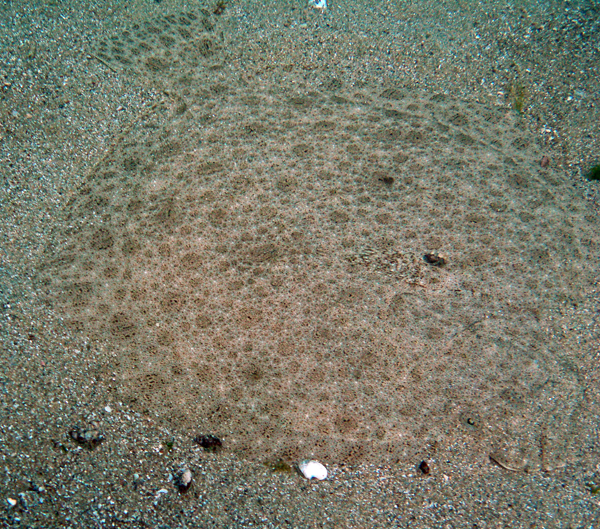

Let's start with a dive in early spring – let’s say in April. About this time of year you need a warm wetsuit and a strong desire for underwater adventures. But despite the cold it is worth looking around under water. It is the time when the Black Sea turbot (Psetta maxima maeotica or Scophthalmus maeoticus) emerges from the depths of the sea and prepares for mating in the shallows. It is a little hard to see turbots during free-diving, as it is a master of disguise and can, like the chameleon, change color in accord with the environment. This makes it difficult to detect it in the short period of time a free-diver has while holding the breath. Another challenge for snorkelers to see turbots is that one needs to be able to dive down to at least 7-10m depth, where turbots usually linger. Breeding period lasts until about mid-June.

Figure 1 Turbot

Figure 1 Turbot

Another interesting event in April and May is the mating act of the wrasses (Symphodus tinca, Symphodus roissali, Symphodus ocellatus and Symphodus cinereus). They are very funny during this period - building nests of sea shells and seaweed and performing interesting "wedding" ceremonies.

Figure 2 Ocellated wrasse (Symphodus ocellatus) in the front

Figure 2 Ocellated wrasse (Symphodus ocellatus) in the front

Another marine species that comes out in early spring - even earlier than turbots - is the sea horse (Hippocampus ramulosus). Sea horses are abundant in the Black Sea, so locals usually don’t pay attention to them. I realized that when I heard the words of a German guy after diving in the Black Sea: "In the Mediterranean you are lucky if you see three seahorses during a dive, and here I saw 25." Sea horses – most beloved by kids - can be found in not very deep water areas with lush aquatic vegetation, mainly between 3 and 10 meters. They cannot change color, but they are very good at imitating algae in behavior.

Figure 3 Sea horse (left), tentacled blenny (Parablennius tentacularis) (right)

Figure 3 Sea horse (left), tentacled blenny (Parablennius tentacularis) (right)

A close relative to the seahorse is the sea needle (Sygnathus tenuirostris). It also prefers living at the bottom with a lot of algae, but it also occurs on sandy beaches. These species are very widespread in the Black Sea and are also found in knee-deep water.

Figure 4 Narrow-snouted pipefish (Syngnathus tenuirostris)

Figure 4 Narrow-snouted pipefish (Syngnathus tenuirostris)

Also widespread in the Black Sea are gobies (family Gobiidae). There are so many in so many varieties that I do not know if anyone in Bulgaria knows all kinds of them. The most famous of them are round goby (Neogobius melanostomus) and knout goby (Mesogobius batrachocephalus). The knout goby is the largest species of the gobiidae family and reaches 40 cm in length and 500 g in weight. The round goby can only reach half this size. It is easily recognizable under water due to the black spot on the front-dorsal fin. Gobies live in the benthic zone and are found everywhere (rocks and sand). To meet a knout goby, however, it can be necessary to dive a little deeper - say ca. 10 meters.

Figure 5 Knout goby (Mesogobius batrachocephalus)

Figure 5 Knout goby (Mesogobius batrachocephalus)

A slightly more exotic version of gobies are blennies (family Blenniidae). Unlike gobies they are not edible, and they are more colorful. They appear in shallow depths - mostly about 3-5 m. My favorite blenny is the peacock blenny (Salaria pavo). The male is very interesting and colorful and has a crest on its head, which makes it look even more exotic.

Figure 6 Peacock blenny

Figure 6 Peacock blenny

Leaving gobies and blennies behind, it is worth taking a look at the seabed to find another sea bottom dweller - the sand sole (Pegusa lascaris). It looks like a turbot, but is much smaller and its body is elongated. It cannot change color like a turbot, but its body is brownish yellow or reddish brown with obscure pale blotches and specks blending it well with the sandy bottom. Sand soles are widespread in the Black Sea and live in shallow water. According to my observations they are mostly active at night.

Figure 7 Sand sole

Figure 7 Sand sole

Besides sand soles, you can see other interesting creatures of the Black Sea at night: the black scorpionfish (Scorpaena porcus), Roche’s snake blenny (Ophidion rochei) or the greater weever (Trachinus draco). They are all night predators, and it is less likely to come across them at daytime. Scorpionfish and weevers are equipped with venomous spines on the body, so one must be careful with them (their venom is not deadly). The snake blenny looks like a small eel. When I saw it for the first time, I thought it was an eel. After I showed one of my underwater photos to the biologists of the Institute of Oceanology in Varna, they explained with a smile that I had captured the common Roche’s snake blenny, it not being a rare species in the Black Sea at all.

Figure 8 Black scorpionfish (left) and Roche’s snake blenny (right)

Figure 8 Black scorpionfish (left) and Roche’s snake blenny (right)

Besides fish, you can see many other beautiful organisms at night - like sea anemones (Actinia equina). During the day, they are just small brown circular spots on the rocks, but at night they turn into blooming flowers. Other not particularly attractive organisms during the day that are fixed on rocks are blue sponges (Dysidea etheria). Sometimes it happens that they grow to a height so that I am tempted to call them the Black Sea corals (biologically speaking this definition is not correct).

Figure 9 Blue sponges (left) and sea anemones (right)

Figure 9 Blue sponges (left) and sea anemones (right)

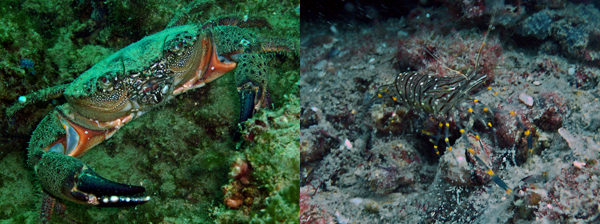

It is also worth to pay attention to the crustaceans in the Black Sea. The most famous is the grass prawn (Palaemon elegans), and the largest of them is the warty crab (Eriphia verrucosa). The grass prawn is seemingly colorless and dull, but looking at it more closely it becomes very colorful and interesting. It is a very common species in the Black Sea and can occur at any depth. The warty crab is very aggressive and scary. I've never been pinched by a warty crab but it would surely hurt. It inhabits rocky bottoms around 4 m and deeper.

Figure 10 Warty crab (left) and grass prawn (right)

Figure 10 Warty crab (left) and grass prawn (right)

A favorite target of spear fishermen are mullets (Mugilidae). There are many varieties of mullets in the Black Sea and in most cases it is impossible to determine during the dive, which species was encountered. The variations known to me are the flathead mullet (Mugil cephalus), leaping mullet (Liza saliens) and the golden grey mullet (Liza aurata). It often happens during a dive that one can see a little school of small mullets "grazing" at the bottom looking for larvae and small algae. The largest kind of mullets is the flathead mullet reaching 65 cm in length and 4 kg in weight.

Figure 11 Leaping mullet

Figure 11 Leaping mullet

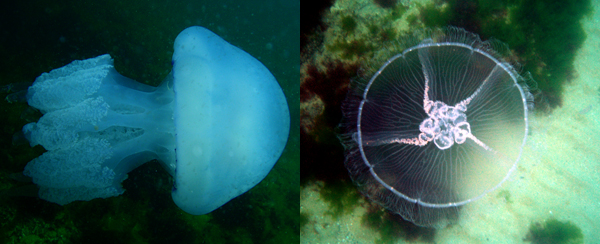

Another interesting sea creature, although not very pleasant for tourists, is the jellyfish. The biggest of them and the most popular is the barrel jellyfish (Rhizostoma pulmo). Another common species is the moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita). One should be careful with the barrel jellyfish because it is covered with skin-irritating mucus. It usually doesn't burn on the palms, but it can cause redness and a slight burning comparable to a nettle sting on more delicate parts of the skin. My advice is to not touch your face with hands that had touched barrel jellyfish before. The moon jellyfish is fortunately harmless and even cute, but not when it is in large swarms.

Figure 12 Jellyfish: barrel jellyfish (left) and moon jellyfish (right)

Figure 12 Jellyfish: barrel jellyfish (left) and moon jellyfish (right)

Finally I would like to mention the veined rapa whelk (Rapana venosa). It is the largest sea snail in the Black Sea, but it is an invader from distant seas, probably introduced as eggs attached to vessels. It is not particularly beautiful, there is a plenty of them, and it is a carnivore that feeds on the blue mussel (Mytilus edulis), which is considered to be the filter of the Black Sea.

Figure 13 Veined rapa whelk

Figure 13 Veined rapa whelk

This concludes my guide to the Black Sea. There are many other inhabitants of our sea that I have not mentioned, such as the common stingray (Dasyatis pastinaca), the tub gurnard (Trigla lucerna), the European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax), the brown meagre (Sciaena umbra), the picked dogfish (Squalus acanthias), the Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda), the horse mackerel (Trachurus mediterraneus ponticus), the garfish (Belone belone) etc. They should be subject of an advanced guide.

As a closing remark, I would like to appeal to all spear fishermen to replace their spear with an underwater camera so that our children also have a variety of nature to see in the Black Sea.